PLEASE LOGIN TO SEE ANYTHING.

This measure is inconvenient, yes, but necessary at present.

Click below for more information.

EVERYTHING IS MARKED UNREAD!!

2024 LOGIN/Posting ISSUES

If you cannot Debauch because you get an IP blacklist error, try Debauching again time. It may work immediately, it may take a few attempts. It will work eventually, I don't think I had to click debauch more than three times. Someone is overzealous at our hosting company, but only on the first couple of attempts.

If you have problems logging in, posting, or doing anything else, please get in touch.

You know the email (if you don't, see in the registration info below), you know where to find the Administerrerrerr on the Midget Circus.

Some unpleasant miscreant was firing incessant database queries at our server, which forced the Legal Department of our hosting company, via their Abuse subdivision, to shut us down. No I have none.

All I can do it button the hatches, and tighten up a few things. Such as time limits on how long you may take to compose a post and hit Debauch! As of 24/01/10, I've set that at 30 minutes for now.

To restrict further overloads, any unregistered users had to be locked out.

How do we know who is or isn't an unregistered user?

By forcing anyone who wants in to Log In.

Is that annoying?

Yes. But there's only so much the Administerrerrerr can do to keep this place running.

Again, if you have any problems: get in touch.

REGISTRATION! NEW USERS!

This measure is inconvenient, yes, but necessary at present.

Click below for more information.

EVERYTHING IS MARKED UNREAD!!

click her for the instant fix

Show

First fix:

Because the board got shutdown again because of a load of database, I had to fettle with the settings again.

As part of that, the server no longer stores what topics you have or haven't read.

IT IS STILL RECORDED!

But now, that information lives in a delicious cookie, rather than the forum database.

Upside: this should reduce the load of database.

Downside: if you use multiple devices to access the board, or you reject delicious cookies, you won't always have that information cookie. But the New Posts feature should take care of that.

PLEASE NOTIFY THE ADMINISTERRERRERR ABOUT ANY PROBLEMS!

- open the menu at the top

- hit New Posts to see what's actually new and browse the new stuff from there

- go back to the Forum Index

- open the menu at the top again

- click Mark forums read

this will zero the unread anything for you, so you can strive forth into the exciting world of the new cookie thing.

Because the board got shutdown again because of a load of database, I had to fettle with the settings again.

As part of that, the server no longer stores what topics you have or haven't read.

IT IS STILL RECORDED!

But now, that information lives in a delicious cookie, rather than the forum database.

Upside: this should reduce the load of database.

Downside: if you use multiple devices to access the board, or you reject delicious cookies, you won't always have that information cookie. But the New Posts feature should take care of that.

PLEASE NOTIFY THE ADMINISTERRERRERR ABOUT ANY PROBLEMS!

2024 LOGIN/Posting ISSUES

Click if you have a problem.

Show

If you cannot Debauch because you get an IP blacklist error, try Debauching again time. It may work immediately, it may take a few attempts. It will work eventually, I don't think I had to click debauch more than three times. Someone is overzealous at our hosting company, but only on the first couple of attempts.

If you have problems logging in, posting, or doing anything else, please get in touch.

You know the email (if you don't, see in the registration info below), you know where to find the Administerrerrerr on the Midget Circus.

Some unpleasant miscreant was firing incessant database queries at our server, which forced the Legal Department of our hosting company, via their Abuse subdivision, to shut us down. No I have none.

All I can do it button the hatches, and tighten up a few things. Such as time limits on how long you may take to compose a post and hit Debauch! As of 24/01/10, I've set that at 30 minutes for now.

To restrict further overloads, any unregistered users had to be locked out.

How do we know who is or isn't an unregistered user?

By forcing anyone who wants in to Log In.

Is that annoying?

Yes. But there's only so much the Administerrerrerr can do to keep this place running.

Again, if you have any problems: get in touch.

REGISTRATION! NEW USERS!

Registration Information

Show

Automatic registration is disabled for security reasons.

But fear not!

You can register!

Option the First:

Please drop our fearless Administerrerrerr a line.

Tell him who you are, that you wish to join, and what you wish your username to be. The Administerrerrerr will get back to you. If you're human, and you're not a damn spammer, expect a reply within 24 hoursish. Usually quicker, rarely slower.

Unfortunately, the Contact Form is being a total primadonna right now, so please send an email to the obvious address.

Posting this address in clear text is just the "on" switch for spambots, but here is a hint.

Option the Second:

Find us on Facebook, in the magnificent

Umah Thurman Midget Circus

Join up there, or just drop the modmins a message. They will pass any request on to the Administerrerrerr for this place.

But fear not!

You can register!

Option the First:

Please drop our fearless Administerrerrerr a line.

Tell him who you are, that you wish to join, and what you wish your username to be. The Administerrerrerr will get back to you. If you're human, and you're not a damn spammer, expect a reply within 24 hoursish. Usually quicker, rarely slower.

Unfortunately, the Contact Form is being a total primadonna right now, so please send an email to the obvious address.

Posting this address in clear text is just the "on" switch for spambots, but here is a hint.

Option the Second:

Find us on Facebook, in the magnificent

Umah Thurman Midget Circus

Join up there, or just drop the modmins a message. They will pass any request on to the Administerrerrerr for this place.

Food Inc. documentary

- Groove

- El Monstro De La Noche

- Location: Northern NY (The most North-ist part)

Food Inc. documentary

I've been waiting for this:

<object width="425" height="344"><param name="movie" value="http://www.youtube.com/v/QqQVll-MP3I&co ... ram><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true"></param><embed src="http://www.youtube.com/v/QqQVll-MP3I&co ... edded&fs=1" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" allowfullscreen="true" width="425" height="344"></embed></object>

Anyone want to start a farm co-op?

<object width="425" height="344"><param name="movie" value="http://www.youtube.com/v/QqQVll-MP3I&co ... ram><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true"></param><embed src="http://www.youtube.com/v/QqQVll-MP3I&co ... edded&fs=1" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" allowfullscreen="true" width="425" height="344"></embed></object>

Anyone want to start a farm co-op?

#############

"My new spleen came from a guy who liked the motorcycle" - Philip J. Frye

09 KLR (Gonzo)

03 SV650 (Crouchy Von Spine-Mangler)

02 KTM 640 (The Homewrecker)

"My new spleen came from a guy who liked the motorcycle" - Philip J. Frye

09 KLR (Gonzo)

03 SV650 (Crouchy Von Spine-Mangler)

02 KTM 640 (The Homewrecker)

-

motorpsycho67

- Double-dip Diogenes

- Location: City of Angels

- Sisyphus

- Rigging the Ancient Mariner

- Location: The Muckworks

- Contact:

-

motorpsycho67

- Double-dip Diogenes

- Location: City of Angels

- Groove

- El Monstro De La Noche

- Location: Northern NY (The most North-ist part)

- SSCAM

- Barista of Doom

- Location: The Fifth Circle

- Groove

- El Monstro De La Noche

- Location: Northern NY (The most North-ist part)

Talk to these folks, they'll hook you right up: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MonsantosupersweetcoolawesomeMatt wrote:I'm against you on this. I demand a certain (read: high) level of toxins, poisons and enhancing chemicals in my food.

Fuck organics.

Evil fuckers!

#############

"My new spleen came from a guy who liked the motorcycle" - Philip J. Frye

09 KLR (Gonzo)

03 SV650 (Crouchy Von Spine-Mangler)

02 KTM 640 (The Homewrecker)

"My new spleen came from a guy who liked the motorcycle" - Philip J. Frye

09 KLR (Gonzo)

03 SV650 (Crouchy Von Spine-Mangler)

02 KTM 640 (The Homewrecker)

-

rolly

- Tim Horton hears a Who?

- Location: Greater Trauma Area

- Contact:

-

Davros

- It's Just a Nickname

- Location: Skaro

- Contact:

Toxic supplements are what keep me so robust. How else are you gonna build up a tolerance?If you don't build it up, the first accidental exposure to something unpleasant, you're either really sick or dead.

It's kind of like a vaccine

It's kind of like a vaccine

If you set up a fictional universe then you can argue that certain things are, or are not, logical and consistent within that universe. Of course the fact you might be able to show something is indeed logical and consistent in a fictional world says nothing about reality.

- nate

- Maltov Rattlecan

- Location: Michigan

[quote]I'm against you on this. I demand a certain (read: high) level of toxins, poisons and enhancing chemicals in my food.

Fuck organics.[/quote]

absolutely correct. If it's not "Round Up Ready" I don't want it...

Also, Could someone explain why I can't properly quote... Maybe I'm dense??

Fuck organics.[/quote]

absolutely correct. If it's not "Round Up Ready" I don't want it...

Also, Could someone explain why I can't properly quote... Maybe I'm dense??

And he thought that, had he been wearing his guns, he may well have drawn one and put a bullet into her cold and whoring little heart.

- Timmay

- Magnum Jihad

- Location: KCMO

- Contact:

I have a mini uber garden growing in my kitchen right now. I'm sure my neighbors think I'm growing the sticky but it's really just brocolli, peas, cantalope, lettuce, kale... and a shit ton of other grub. We're building raised beds out side (fucking underground cables... keepin the farmer down man!). After the the inside stuff gets bigger we transplan t it outside.

Read your farmers almanac and plan ahead.

oh and I have a dead cow and pig in my basement. Grass fed of course. It's pretty cheap when you step back and think about what you'd spend per week on meat. I think we spent $800 on a whole cow. We kept half ans sold the other half. Do you know how long it takes to eat 150 lbs of ground beef? Sure it's not all steaks, and you have to get creative with the shanks, and soup bones, but thats what Alton Brown is for (motorcycles and recipes).

shit I didn't mean to babble

Read your farmers almanac and plan ahead.

oh and I have a dead cow and pig in my basement. Grass fed of course. It's pretty cheap when you step back and think about what you'd spend per week on meat. I think we spent $800 on a whole cow. We kept half ans sold the other half. Do you know how long it takes to eat 150 lbs of ground beef? Sure it's not all steaks, and you have to get creative with the shanks, and soup bones, but thats what Alton Brown is for (motorcycles and recipes).

shit I didn't mean to babble

- Photo

- Bacon Torpedo

- Location: Aurora, CO

Re: Food Inc. documentary

Me!!! I'm tired of poisoning people's minds...I now want to poison their whole BODY.GrooveMonkey wrote:Anyone want to start a farm co-op?

Actually, that looks like a really good show. Some time ago, Rhinoviper posted some random jobs available at an Arkansas chicken processing plant she was consulting for. One of the job opportunities she listed was for "anus puller". I haven't touched a packaged chicken since...in the anus, or anywhere else.

I've been on the kill floor at a meat packing plant before - that didn't do my beef appetite too much good either. The killing methods weren't what put me off, either - it was the "allowable" amount of filth that passed USDA inspection that did me in. I'm still no veggie freak, but it certainly curbed my meatlust. I'll never set foot inside a bacon factory. Ever. That would be like proving to me that Santa doesn't exist.

"Brought to you, by Carl's Jr."

- rubber buccaneer

- Magnum Jihad

nate wrote:absolutely correct. If it's not "Round Up Ready" I don't want it...I'm against you on this. I demand a certain (read: high) level of toxins, poisons and enhancing chemicals in my food.

Fuck organics.

Also, Could someone explain why I can't properly quote... Maybe I'm dense??

Code: Select all

[quote="here goes the name o' teh terrerrist you're quoting"][quote]I'm against you on this. I demand a certain (read: high) level of toxins, poisons and enhancing chemicals in my food.

Fuck organics.[/quote]

absolutely correct. If it's not "Round Up Ready" I don't want it...

Also, Could someone explain why I can't properly quote... Maybe I'm dense??[/quote] ———————

keeper of the man-t-hose

keeper of the man-t-hose

- rubber buccaneer

- Magnum Jihad

bump ...

http://www.hulu.com/watch/67878/the-future-of-food

The Future Of Food offers an in-depth investigation into the disturbing truth behind engineered foods that have quietly filled U.S. grocery store shelves for the past decade.

http://www.hulu.com/watch/67878/the-future-of-food

The Future Of Food offers an in-depth investigation into the disturbing truth behind engineered foods that have quietly filled U.S. grocery store shelves for the past decade.

———————

keeper of the man-t-hose

keeper of the man-t-hose

- Jonny

- Sausage Pirate

- Location: Anakie Rd.

Re: Food Inc. documentary

Bacon Santa!Photo wrote:I'll never set foot inside a bacon factory. Ever. That would be like proving to me that Santa doesn't exist.

I'm amazed at some of the jobs out there that I NEVER knew existed. Just imagine, sitting at a bar, and you strike up a conversation with a cute, virile young lass. Things are going exceedingly well and you end up buying each other drinks. Then she says "I work in graphic design, what do you do?"

"Uhhhhh... I pull the anus out of dead chickens".

"Yeah, ok. I'm leaving now".

- Photo

- Bacon Torpedo

- Location: Aurora, CO

*burps, then resuscitates thread*

I finally got to see this movie this weekend. It's a VERY good show - not from the perspective of someone who likes to eat, but at how easy it is for our bread basket to be broken. I'd read articles about corporate control, but this show goes into a bit of detail about how easily the ag conglomerates are taking out the last independent food growers, gangsta-style. It pretty much spells out the death of wholesome, and un-patented foods in the world.

I'd seen a show on the Documentary Channel last week about India's food production (or lack thereof). There was a talking head from their ministry of health describing how the food corporations were cracking down on growers who weren't using their seeds...I watched her describe how corporate-patented seeds are being used to squeeze out the last of the "unmodified" public seed crops in her country. She continued to say that unless her government did something to prevent attacks on private farms, there would be no legal way to grow food in her country, without having to pay a royalty to global food conglomerates (like ConAgra, Archer-Daniels-Midland, and Monsanto). Famine would follow, as most small farmers have all their wealth in their land, not in cash from their crops. I thought, "Well, this is India. There's a giant gap between wealth and poverty, so it would be easy for corporations to buy off India's politicians. That couldn't happen in the U.S." Wrong.

In Food, Inc., three farmers gave testimony that Monsanto hired security squads to investigate and prevent farmers from re-using their "public", un-patented seeds for planting soybeans. Their tactics were extremely invasive and offensive, to the point that the farmers were smothered out of existence if they didn't become Monsanto-based farmers, and adhere to their strict seed-control guidelines. GMO's (Genetically Modified Organisms) are considered private property, and to farm with free "public seeds" in proximity to a farm that uses GMO's puts a farmer at risk for contamination by the GMO seeds. ANY farmer caught with an "infestation" of GMO plants on his or her property is GUILTY of patent-infringement, and subject to extreme legal harassment by Monsanto. It becomes the burden of the "public" seed farmer to prove that they didn't receive these seeds illicitly, and that they must prove that they have taken steps to guarantee a GMO-free crop. Legal action against a local farmer by a corporate giant almost ensures their death, financially.

There were 2 seed cleaners documented on the show (of only a handful left in the country), who were being legally forced out of business, because the corporation did NOT want to allow them to continue in their trade of aiding farmers to use "public" soybean seeds. Over 98% of the U.S.-grown soybeans are grown using a Monsanto-patented, genetically-modified Roundup(tm) resistant seed. Considering how many uses the soybean has in our processed food systems, that's some serious power in the hands of a monopoly.

I would HIGHLY recommend that you see this show. Not because I would like to force politically-correct food down your gullets, but because it takes info from the producers' mouths about how powerful the Global Agricultural business has become, when it comes to what you eat. (Even what you say about what you eat). Scary stuff.

Scary stuff.

I finally got to see this movie this weekend. It's a VERY good show - not from the perspective of someone who likes to eat, but at how easy it is for our bread basket to be broken. I'd read articles about corporate control, but this show goes into a bit of detail about how easily the ag conglomerates are taking out the last independent food growers, gangsta-style. It pretty much spells out the death of wholesome, and un-patented foods in the world.

I'd seen a show on the Documentary Channel last week about India's food production (or lack thereof). There was a talking head from their ministry of health describing how the food corporations were cracking down on growers who weren't using their seeds...I watched her describe how corporate-patented seeds are being used to squeeze out the last of the "unmodified" public seed crops in her country. She continued to say that unless her government did something to prevent attacks on private farms, there would be no legal way to grow food in her country, without having to pay a royalty to global food conglomerates (like ConAgra, Archer-Daniels-Midland, and Monsanto). Famine would follow, as most small farmers have all their wealth in their land, not in cash from their crops. I thought, "Well, this is India. There's a giant gap between wealth and poverty, so it would be easy for corporations to buy off India's politicians. That couldn't happen in the U.S." Wrong.

In Food, Inc., three farmers gave testimony that Monsanto hired security squads to investigate and prevent farmers from re-using their "public", un-patented seeds for planting soybeans. Their tactics were extremely invasive and offensive, to the point that the farmers were smothered out of existence if they didn't become Monsanto-based farmers, and adhere to their strict seed-control guidelines. GMO's (Genetically Modified Organisms) are considered private property, and to farm with free "public seeds" in proximity to a farm that uses GMO's puts a farmer at risk for contamination by the GMO seeds. ANY farmer caught with an "infestation" of GMO plants on his or her property is GUILTY of patent-infringement, and subject to extreme legal harassment by Monsanto. It becomes the burden of the "public" seed farmer to prove that they didn't receive these seeds illicitly, and that they must prove that they have taken steps to guarantee a GMO-free crop. Legal action against a local farmer by a corporate giant almost ensures their death, financially.

There were 2 seed cleaners documented on the show (of only a handful left in the country), who were being legally forced out of business, because the corporation did NOT want to allow them to continue in their trade of aiding farmers to use "public" soybean seeds. Over 98% of the U.S.-grown soybeans are grown using a Monsanto-patented, genetically-modified Roundup(tm) resistant seed. Considering how many uses the soybean has in our processed food systems, that's some serious power in the hands of a monopoly.

I would HIGHLY recommend that you see this show. Not because I would like to force politically-correct food down your gullets, but because it takes info from the producers' mouths about how powerful the Global Agricultural business has become, when it comes to what you eat. (Even what you say about what you eat).

"Brought to you, by Carl's Jr."

- guitargeek

- Master Metric Necromancer

- Location: East Goatfuck, Oklahoma

- Contact:

http://www.utmc-forum.org/pub/viewtopic ... 7209#77209

http://www.utmc-forum.org/pub/viewtopic ... 177#140177

http://www.utmc-forum.org/pub/viewtopic ... 177#140177

Elitist, arrogant, intolerant, self-absorbed.

Midliferider wrote:Wish I could wipe this shit off my shoes but it's everywhere I walk. Dang.

Pattio wrote:Never forget, as you enjoy the high road of tolerance, that it is those of us doing the hard work of intolerance who make it possible for you to shine.

xtian wrote:Sticking feathers up your butt does not make you a chicken

- guitargeek

- Master Metric Necromancer

- Location: East Goatfuck, Oklahoma

- Contact:

Also...

July 5, 2009

Street Farmer

By ELIZABETH ROYTE

Will Allen, a farmer of Bunyonesque proportions, ascended a berm of wood chips and brewer’s mash and gently probed it with a pitchfork. “Look at this,” he said, pleased with the treasure he unearthed. A writhing mass of red worms dangled from his tines. He bent over, raked another section with his fingers and palmed a few beauties.

It was one of those April days in Wisconsin when the weather shifts abruptly from hot to cold, and Allen, dressed in a sleeveless hoodie — his daily uniform down to 20 degrees, below which he adds another sweatshirt — was exactly where he wanted to be. Show Allen a pile of soil, fully composted or still slimy with banana peels, and he’s compelled to scoop some into his melon-size hands. “Creating soil from waste is what I enjoy most,” he said. “Anyone can grow food.”

Like others in the so-called good-food movement, Allen, who is 60, asserts that our industrial food system is depleting soil, poisoning water, gobbling fossil fuels and stuffing us with bad calories. Like others, he advocates eating locally grown food. But to Allen, local doesn’t mean a rolling pasture or even a suburban garden: it means 14 greenhouses crammed onto two acres in a working-class neighborhood on Milwaukee’s northwest side, less than half a mile from the city’s largest public-housing project.

And this is why Allen is so fond of his worms. When you’re producing a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of food in such a small space, soil fertility is everything. Without microbe- and nutrient-rich worm castings (poop, that is), Allen’s Growing Power farm couldn’t provide healthful food to 10,000 urbanites — through his on-farm retail store, in schools and restaurants, at farmers’ markets and in low-cost market baskets delivered to neighborhood pickup points. He couldn’t employ scores of people, some from the nearby housing project; continually train farmers in intensive polyculture; or convert millions of pounds of food waste into a version of black gold.

With seeds planted at quadruple density and nearly every inch of space maximized to generate exceptional bounty, Growing Power is an agricultural Mumbai, a supercity of upward-thrusting tendrils and duct-taped infrastructure. Allen pointed to five tiers of planters brimming with salad greens. “We’re growing in 25,000 pots,” he said. Ducking his 6-foot-7 frame under one of them, he pussyfooted down a leaf-crammed aisle. “We grow a thousand trays of sprouts a week; every square foot brings in $30.” He headed toward the in-ground fish tanks stocked with tens of thousands of tilapia and perch. Pumps send the dirty fish water up into beds of watercress, which filter pollutants and trickle the cleaner water back down to the fish — a symbiotic system called aquaponics. The watercress sells for $16 a pound; the fish fetch $6 apiece.

Onward through the hoop houses: rows of beets and chard. Out back: chickens, ducks, heritage turkeys, goats, beehives. While Allen narrated, I nibbled the scenery — spinach, arugula, cilantro.

If inside the greenhouse was Eden, outdoors was, as Allen explained on a drive through the neighborhood, “a food desert.” Scanning the liquor stores in the strip malls, he noted: “From the housing project, it’s more than three miles to the Pick’n Save. That’s a long way to go for groceries if you don’t have a car or can’t carry stuff. And the quality of the produce can be poor.” Fast-food joints and convenience stores selling highly processed, high-calorie foods, on the other hand, were locally abundant. “It’s a form of redlining,” Allen said. “We’ve got to change the system so everyone has safe, equitable access to healthy food.”

Propelled by alarming rates of diabetes, heart disease and obesity, by food-safety scares and rising awareness of industrial agriculture’s environmental footprint, the food movement seems finally to have met its moment. First Lady Michelle Obama and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack have planted organic vegetable gardens. Roof gardens are sprouting nationwide. Community gardens have waiting lists. Seed houses and canning suppliers are oversold.

Allen, too, has achieved a certain momentum for his efforts to bring the good-food movement to the inner city. In the last several years, he has become a darling of the foundation world. In 2005, he received a $100,000 Ford Foundation leadership grant. In 2008, the MacArthur Foundation honored Allen with a $500,000 “genius” award. And in May, the Kellogg Foundation gave Allen $400,000 to create jobs in urban agriculture.

Today Allen is the go-to expert on urban farming, and there is a hunger for his knowledge. When I visited Growing Power, Allen was conducting a two-day workshop for 40 people: each paid $325 to learn worm composting, aquaponics construction and other farm skills. “We need 50 million more people growing food,” Allen told them, “on porches, in pots, in side yards.” The reasons are simple: as oil prices rise, cities expand and housing developments replace farmland, the ability to grow more food in less space becomes ever more important. As Allen can’t help reminding us, with a mischievous smile, “Chicago has 77,000 vacant lots.”

Allen led the composting group to a pair of wooden bins and instructed his students to load them with hay. “O.K., you’ve got your carbon,” he said. “Where are you going to get your nitrogen?”

“Food waste,” a young man offered, wiping his brow. Allen pointed him toward a mound of expired asparagus collected from a wholesaler. As the participants layered the materials in a bin, Allen drilled them: “How much of that food is solid versus water weight?” “Why do we water the compost?” The farmers in training hung on every word.

If Allen at times seems a bit weary — he recites his talking points countless times a day — he comes alive when he’s digging, seeding and watering. His body straightens, and his face brightens. “Sitting in my office isn’t a very comfortable thing for me,” he told me later, seated in his office. “I want to be out there doing physical stuff.”

Which includes basic research. Warned by experts that his red wrigglers would freeze during Milwaukee’s long winter, Allen studied the worms for five years, learning their food and shelter preferences. “I’d run my experiments over and over and over — just like an athlete operates.” Then he worked out systems for procuring wood chips from the city and food scraps from markets and wholesalers. Last year, he took in six million pounds of spoiled food, which would otherwise rot in landfills and generate methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Every four months, he creates another 100,000 pounds of compost, of which he uses a quarter and sells the rest.

Uncannily, Allen makes such efforts sound simple — fun even. When he mentions that animal waste attracts soldier flies, whose larvae make terrific fish and chicken feed, a dozen people start imagining that growing grubs in buckets of manure might be a good project for them too. “Will has a way of persuading people to do things,” Robert Pierce, a farmer in Madison, Wis., told me. “There’s a spirit in how he says things; you want to be part of his community.”

Allen owes part of his Pied Piper success to his striking physicality and part to his athlete’s confidence — he’s easeful in his skin and, when not barking about nitrogen ratios, incongruously gentle. He told me about his life one afternoon as we drove in his truck, which was sticky with soda and dusted with doughnut powder, to Merton, a suburb of Milwaukee where Growing Power leases a 30-acre plot. “My father was a sharecropper in South Carolina,” Allen said. “He was the eldest boy of 13 children, and he never learned to read.” In the 1930s, he moved near Bethesda, Md. “My mother did domestic work, and my father worked as a construction laborer. But he rented a small plot to farm.”

A talented athlete, Allen wasn’t allowed to practice sports until he finished his farm chores. “I had to be in bed early, and I thought, There’s got to be something better than this.” For a while, there was. Allen accepted a basketball scholarship from the University of Miami. There, he married his college sweetheart, Cyndy Bussler. After graduating, he played professionally, briefly in the American Basketball Association in Florida and then for a few seasons in Belgium. In his free time, Allen would drive around the countryside, where he couldn’t help noticing the compost piles.

“I started hanging out with Belgian farmers,” Allen said. “I saw how they did natural farming,” much as his father had. Something clicked in his mind. He asked his team’s management, which provided housing for players, if he could have a place with a garden. Soon he had 25 chickens and was growing the familiar foods of his youth — peas, beans, peanuts — outside Antwerp. “I just had to do it,” he said. “It made me happy to touch the soil.” On holidays, he cooked feasts for his teammates. He gave away a lot of eggs.

After retiring from basketball in 1977, when he was 28, Allen settled with his wife and three children in Oak Creek, just south of Milwaukee, where Cyndy’s family owned some farmland. “No one was using that land, but I had the bug to grow food,” Allen said. As his father did, Allen insisted that his children contribute to the household income. “We went right to the field at the end of the school day and during summer breaks,” recalled his daughter, Erika Allen, who now runs Growing Power’s satellite office in Chicago. “And let’s be clear: This was farm labor, not chores.”

Allen grew food for his family and sold the excess at Milwaukee’s farmers’ markets and in stores. Meanwhile, he worked as a district manager for Kentucky Fried Chicken, where he won sales awards. “It was just a job,” he said. “I was aware it wasn’t the greatest food, but I also knew that people didn’t have a lot of choice about where to eat: there were no sit-down restaurants in that part of the city.”

In 1987, Allen took a job with Procter & Gamble, where he won a marketing award for selling paper goods to supermarkets. “The job was so easy I could do it in half a day,” he says now. That left more time to grow food. By now, Allen was sharing his land with Hmong farmers, with whom he felt some kinship after concluding that white shoppers were spurning their produce at the farmers’ market. Allen was also donating food to a local food pantry. “I didn’t like the idea of people eating all that canned food, that salty stuff.” When he brought in his greens, he said, “it was the No. 1 item selected off that carousel — it was like you couldn’t keep them in.”

After a restructuring in 1993, P&G shifted Allen to analyzing which products sold best in supermarkets. He was good at that too: “I won sales awards six times in one year.”

Driving across his Merton field, Allen smiled. Suddenly, I got it: Allen was a genius at selling — fried chicken, Pampers, arugula, red wrigglers, you name it. He could push his greens into corporate cafeterias, persuade the governor to help finance the construction of an anaerobic digester, wheedle new composting sites from urban landlords, persuade Milwaukee’s school board to buy his produce for its public schools and charm the blind into growing sprouts. (“I was cutting sprouts in the dark one night,” Allen said, “and I realized you don’t need sight to do this.”)

After parking his truck at the field’s edge, Allen made an arthritic beeline for a mound of compost. “Oh, this is good,” he said, digging in with his hands. “Unbelievable.” He saluted a few volunteers, whom he had appointed to pluck shreds of plastic from the compost under the hot noonday sun. He turned to scan the field, dotted with large farm-unfriendly rocks.

The rocks gave me pause: didn’t millions of Americans leave farms for good reason? The work is hard, nature can be cruel and the pay is low; most small farmers work off-farm to make ends meet. The appeal of such labor to people already working low-wage, long-hour jobs — the urban dwellers Allen most wants to reach — is not immediately apparent. And there is something almost fanciful in exhorting a person to grow food when he lives in an apartment or doesn’t have a landlord’s permission to garden on the roof or in an empty lot.

“Not everyone can grow food,” Allen acknowledged. But he offers other ways of engaging with the soil: “You bring 30 people out here, bring the kids and give them good food,” he said, “and picking up those rocks is a community event.”

Of course, if rock picking or worm tending — either here or in a community garden — doesn’t attract his Milwaukee neighbors, it’s easy enough for them to order a market basket or shop at his retail store, which happens to sell fried pork skin as well as collard greens. “Culturally appropriate foods,” Allen calls them. And the doughnuts in his truck? “I’m no purist about food, and I don’t ask anyone else to be,” he said, laughing. “I work 17 hours a day; sometimes I need some sugar!”

This nondogmatic approach may be one of Allen’s most appealing qualities. His essential view is that people do the best they can: if they don’t have any better food choices than KFC, well, O.K. But let’s work on changing that. If they don’t know what to do with okra, Growing Power stands ready to help. And if their great-grandparents were sharecroppers and they have some bad feelings about the farming life, then Allen has something to offer there too: his personal example and workshops geared toward empowering minorities. “African-Americans need more help, and they’re often harder to work with because they’ve been abused and so forth,” Allen said. “But I can break through a lot of that very quickly because a lot of people of color are so proud, so happy to see me leading this kind of movement.”

If there’s no place in the food movement for low- and middle-income people of all races, says Tom Philpott, food editor of Grist.org and co-founder of the North Carolina-based Maverick Farms, “we’ve got big problems, because the critics will be proven right — that this is a consumption club for people who’ve traveled to Europe and tasted fine food.”

In 1993, Allen, looking to grow indoors during the winter and to sell food closer to the city, bought the Growing Power property, a derelict plant nursery that was in foreclosure. He had no master plan. “I told the city I’d hire kids and teach them about food systems,” he said. Before long, community and school groups were asking for his help starting gardens. He rarely said no. But after years of laboring on his own and beginning to feel burned out, he agreed to partner with Heifer International, the sustainable-agriculture charity. “They were looking for youth to do urban ag. When they learned I had kids and that I had land, their eyes lit up.” Heifer taught Allen fish and worms, and together they expanded their training programs.

Employing locals to grow food for the hungry on neglected land has an irresistible appeal, but it’s not clear yet whether Growing Power’s model can work elsewhere. “I know how to make money growing food,” Allen asserts. But he’s also got between 30 and 50 employees to pay, which makes those foundation grants — and a grant-writer — essential. Growing Power also relies on large numbers of volunteers. All of which perhaps explains why other urban farmers have not yet replicated Growing Power’s scale or its unique social achievements.

So no, Growing Power isn’t self-sufficient. But neither is industrial agriculture, which relies on price supports and government subsidies. Moreover, industrial farming incurs costs that are paid by society as a whole: the health costs of eating highly processed foods, for example, or water pollution. Nor can Growing Power be compared to other small farms, because it provides so many intangible social benefits to those it reaches. “It’s not operated as a farm,” said Ian Marvy, executive director of Brooklyn’s Added Value farm, which shares many of Growing Power’s core values but produces less food. “It has a social, ecological and economic bottom line.” That said, Marvy says that anyone can replicate Allen’s technical systems — the worm composting and aquaponics — for relatively little money.

Finished with his business in Merton, Allen sang out his truck window to his plastic-picking volunteers, “Don’t y’all work too hard now.” The future farmers laughed. Allen predicts that because of high unemployment and the recent food scares, 10 million people will plant gardens for the first time this year. But two million of them will eventually drop out, he said, when the potato bugs arrive or the rain doesn’t cooperate. Still, he was sanguine. “The experience will introduce those folks to what a tomato really tastes like, so next time they’ll buy one at their greenmarket. And when we talk about farm-worker rights, we’ll have more advocates for them.”

At a red light on Silver Spring Drive, Allen stopped and eyed the construction equipment beached in front of a dealership. “Look at that front-end loader,” he said admiringly. “That thing isn’t going to sell.” He shook his head and added: “Maybe we can work something out with them. We could make some nice compost with that.”

Elizabeth Royte is the author of “Bottlemania: Big Business, Local Springs, and the Battle over America’s Drinking Water.”

Copyright 2009 The New York Times Company

July 5, 2009

Street Farmer

By ELIZABETH ROYTE

Will Allen, a farmer of Bunyonesque proportions, ascended a berm of wood chips and brewer’s mash and gently probed it with a pitchfork. “Look at this,” he said, pleased with the treasure he unearthed. A writhing mass of red worms dangled from his tines. He bent over, raked another section with his fingers and palmed a few beauties.

It was one of those April days in Wisconsin when the weather shifts abruptly from hot to cold, and Allen, dressed in a sleeveless hoodie — his daily uniform down to 20 degrees, below which he adds another sweatshirt — was exactly where he wanted to be. Show Allen a pile of soil, fully composted or still slimy with banana peels, and he’s compelled to scoop some into his melon-size hands. “Creating soil from waste is what I enjoy most,” he said. “Anyone can grow food.”

Like others in the so-called good-food movement, Allen, who is 60, asserts that our industrial food system is depleting soil, poisoning water, gobbling fossil fuels and stuffing us with bad calories. Like others, he advocates eating locally grown food. But to Allen, local doesn’t mean a rolling pasture or even a suburban garden: it means 14 greenhouses crammed onto two acres in a working-class neighborhood on Milwaukee’s northwest side, less than half a mile from the city’s largest public-housing project.

And this is why Allen is so fond of his worms. When you’re producing a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of food in such a small space, soil fertility is everything. Without microbe- and nutrient-rich worm castings (poop, that is), Allen’s Growing Power farm couldn’t provide healthful food to 10,000 urbanites — through his on-farm retail store, in schools and restaurants, at farmers’ markets and in low-cost market baskets delivered to neighborhood pickup points. He couldn’t employ scores of people, some from the nearby housing project; continually train farmers in intensive polyculture; or convert millions of pounds of food waste into a version of black gold.

With seeds planted at quadruple density and nearly every inch of space maximized to generate exceptional bounty, Growing Power is an agricultural Mumbai, a supercity of upward-thrusting tendrils and duct-taped infrastructure. Allen pointed to five tiers of planters brimming with salad greens. “We’re growing in 25,000 pots,” he said. Ducking his 6-foot-7 frame under one of them, he pussyfooted down a leaf-crammed aisle. “We grow a thousand trays of sprouts a week; every square foot brings in $30.” He headed toward the in-ground fish tanks stocked with tens of thousands of tilapia and perch. Pumps send the dirty fish water up into beds of watercress, which filter pollutants and trickle the cleaner water back down to the fish — a symbiotic system called aquaponics. The watercress sells for $16 a pound; the fish fetch $6 apiece.

Onward through the hoop houses: rows of beets and chard. Out back: chickens, ducks, heritage turkeys, goats, beehives. While Allen narrated, I nibbled the scenery — spinach, arugula, cilantro.

If inside the greenhouse was Eden, outdoors was, as Allen explained on a drive through the neighborhood, “a food desert.” Scanning the liquor stores in the strip malls, he noted: “From the housing project, it’s more than three miles to the Pick’n Save. That’s a long way to go for groceries if you don’t have a car or can’t carry stuff. And the quality of the produce can be poor.” Fast-food joints and convenience stores selling highly processed, high-calorie foods, on the other hand, were locally abundant. “It’s a form of redlining,” Allen said. “We’ve got to change the system so everyone has safe, equitable access to healthy food.”

Propelled by alarming rates of diabetes, heart disease and obesity, by food-safety scares and rising awareness of industrial agriculture’s environmental footprint, the food movement seems finally to have met its moment. First Lady Michelle Obama and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack have planted organic vegetable gardens. Roof gardens are sprouting nationwide. Community gardens have waiting lists. Seed houses and canning suppliers are oversold.

Allen, too, has achieved a certain momentum for his efforts to bring the good-food movement to the inner city. In the last several years, he has become a darling of the foundation world. In 2005, he received a $100,000 Ford Foundation leadership grant. In 2008, the MacArthur Foundation honored Allen with a $500,000 “genius” award. And in May, the Kellogg Foundation gave Allen $400,000 to create jobs in urban agriculture.

Today Allen is the go-to expert on urban farming, and there is a hunger for his knowledge. When I visited Growing Power, Allen was conducting a two-day workshop for 40 people: each paid $325 to learn worm composting, aquaponics construction and other farm skills. “We need 50 million more people growing food,” Allen told them, “on porches, in pots, in side yards.” The reasons are simple: as oil prices rise, cities expand and housing developments replace farmland, the ability to grow more food in less space becomes ever more important. As Allen can’t help reminding us, with a mischievous smile, “Chicago has 77,000 vacant lots.”

Allen led the composting group to a pair of wooden bins and instructed his students to load them with hay. “O.K., you’ve got your carbon,” he said. “Where are you going to get your nitrogen?”

“Food waste,” a young man offered, wiping his brow. Allen pointed him toward a mound of expired asparagus collected from a wholesaler. As the participants layered the materials in a bin, Allen drilled them: “How much of that food is solid versus water weight?” “Why do we water the compost?” The farmers in training hung on every word.

If Allen at times seems a bit weary — he recites his talking points countless times a day — he comes alive when he’s digging, seeding and watering. His body straightens, and his face brightens. “Sitting in my office isn’t a very comfortable thing for me,” he told me later, seated in his office. “I want to be out there doing physical stuff.”

Which includes basic research. Warned by experts that his red wrigglers would freeze during Milwaukee’s long winter, Allen studied the worms for five years, learning their food and shelter preferences. “I’d run my experiments over and over and over — just like an athlete operates.” Then he worked out systems for procuring wood chips from the city and food scraps from markets and wholesalers. Last year, he took in six million pounds of spoiled food, which would otherwise rot in landfills and generate methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Every four months, he creates another 100,000 pounds of compost, of which he uses a quarter and sells the rest.

Uncannily, Allen makes such efforts sound simple — fun even. When he mentions that animal waste attracts soldier flies, whose larvae make terrific fish and chicken feed, a dozen people start imagining that growing grubs in buckets of manure might be a good project for them too. “Will has a way of persuading people to do things,” Robert Pierce, a farmer in Madison, Wis., told me. “There’s a spirit in how he says things; you want to be part of his community.”

Allen owes part of his Pied Piper success to his striking physicality and part to his athlete’s confidence — he’s easeful in his skin and, when not barking about nitrogen ratios, incongruously gentle. He told me about his life one afternoon as we drove in his truck, which was sticky with soda and dusted with doughnut powder, to Merton, a suburb of Milwaukee where Growing Power leases a 30-acre plot. “My father was a sharecropper in South Carolina,” Allen said. “He was the eldest boy of 13 children, and he never learned to read.” In the 1930s, he moved near Bethesda, Md. “My mother did domestic work, and my father worked as a construction laborer. But he rented a small plot to farm.”

A talented athlete, Allen wasn’t allowed to practice sports until he finished his farm chores. “I had to be in bed early, and I thought, There’s got to be something better than this.” For a while, there was. Allen accepted a basketball scholarship from the University of Miami. There, he married his college sweetheart, Cyndy Bussler. After graduating, he played professionally, briefly in the American Basketball Association in Florida and then for a few seasons in Belgium. In his free time, Allen would drive around the countryside, where he couldn’t help noticing the compost piles.

“I started hanging out with Belgian farmers,” Allen said. “I saw how they did natural farming,” much as his father had. Something clicked in his mind. He asked his team’s management, which provided housing for players, if he could have a place with a garden. Soon he had 25 chickens and was growing the familiar foods of his youth — peas, beans, peanuts — outside Antwerp. “I just had to do it,” he said. “It made me happy to touch the soil.” On holidays, he cooked feasts for his teammates. He gave away a lot of eggs.

After retiring from basketball in 1977, when he was 28, Allen settled with his wife and three children in Oak Creek, just south of Milwaukee, where Cyndy’s family owned some farmland. “No one was using that land, but I had the bug to grow food,” Allen said. As his father did, Allen insisted that his children contribute to the household income. “We went right to the field at the end of the school day and during summer breaks,” recalled his daughter, Erika Allen, who now runs Growing Power’s satellite office in Chicago. “And let’s be clear: This was farm labor, not chores.”

Allen grew food for his family and sold the excess at Milwaukee’s farmers’ markets and in stores. Meanwhile, he worked as a district manager for Kentucky Fried Chicken, where he won sales awards. “It was just a job,” he said. “I was aware it wasn’t the greatest food, but I also knew that people didn’t have a lot of choice about where to eat: there were no sit-down restaurants in that part of the city.”

In 1987, Allen took a job with Procter & Gamble, where he won a marketing award for selling paper goods to supermarkets. “The job was so easy I could do it in half a day,” he says now. That left more time to grow food. By now, Allen was sharing his land with Hmong farmers, with whom he felt some kinship after concluding that white shoppers were spurning their produce at the farmers’ market. Allen was also donating food to a local food pantry. “I didn’t like the idea of people eating all that canned food, that salty stuff.” When he brought in his greens, he said, “it was the No. 1 item selected off that carousel — it was like you couldn’t keep them in.”

After a restructuring in 1993, P&G shifted Allen to analyzing which products sold best in supermarkets. He was good at that too: “I won sales awards six times in one year.”

Driving across his Merton field, Allen smiled. Suddenly, I got it: Allen was a genius at selling — fried chicken, Pampers, arugula, red wrigglers, you name it. He could push his greens into corporate cafeterias, persuade the governor to help finance the construction of an anaerobic digester, wheedle new composting sites from urban landlords, persuade Milwaukee’s school board to buy his produce for its public schools and charm the blind into growing sprouts. (“I was cutting sprouts in the dark one night,” Allen said, “and I realized you don’t need sight to do this.”)

After parking his truck at the field’s edge, Allen made an arthritic beeline for a mound of compost. “Oh, this is good,” he said, digging in with his hands. “Unbelievable.” He saluted a few volunteers, whom he had appointed to pluck shreds of plastic from the compost under the hot noonday sun. He turned to scan the field, dotted with large farm-unfriendly rocks.

The rocks gave me pause: didn’t millions of Americans leave farms for good reason? The work is hard, nature can be cruel and the pay is low; most small farmers work off-farm to make ends meet. The appeal of such labor to people already working low-wage, long-hour jobs — the urban dwellers Allen most wants to reach — is not immediately apparent. And there is something almost fanciful in exhorting a person to grow food when he lives in an apartment or doesn’t have a landlord’s permission to garden on the roof or in an empty lot.

“Not everyone can grow food,” Allen acknowledged. But he offers other ways of engaging with the soil: “You bring 30 people out here, bring the kids and give them good food,” he said, “and picking up those rocks is a community event.”

Of course, if rock picking or worm tending — either here or in a community garden — doesn’t attract his Milwaukee neighbors, it’s easy enough for them to order a market basket or shop at his retail store, which happens to sell fried pork skin as well as collard greens. “Culturally appropriate foods,” Allen calls them. And the doughnuts in his truck? “I’m no purist about food, and I don’t ask anyone else to be,” he said, laughing. “I work 17 hours a day; sometimes I need some sugar!”

This nondogmatic approach may be one of Allen’s most appealing qualities. His essential view is that people do the best they can: if they don’t have any better food choices than KFC, well, O.K. But let’s work on changing that. If they don’t know what to do with okra, Growing Power stands ready to help. And if their great-grandparents were sharecroppers and they have some bad feelings about the farming life, then Allen has something to offer there too: his personal example and workshops geared toward empowering minorities. “African-Americans need more help, and they’re often harder to work with because they’ve been abused and so forth,” Allen said. “But I can break through a lot of that very quickly because a lot of people of color are so proud, so happy to see me leading this kind of movement.”

If there’s no place in the food movement for low- and middle-income people of all races, says Tom Philpott, food editor of Grist.org and co-founder of the North Carolina-based Maverick Farms, “we’ve got big problems, because the critics will be proven right — that this is a consumption club for people who’ve traveled to Europe and tasted fine food.”

In 1993, Allen, looking to grow indoors during the winter and to sell food closer to the city, bought the Growing Power property, a derelict plant nursery that was in foreclosure. He had no master plan. “I told the city I’d hire kids and teach them about food systems,” he said. Before long, community and school groups were asking for his help starting gardens. He rarely said no. But after years of laboring on his own and beginning to feel burned out, he agreed to partner with Heifer International, the sustainable-agriculture charity. “They were looking for youth to do urban ag. When they learned I had kids and that I had land, their eyes lit up.” Heifer taught Allen fish and worms, and together they expanded their training programs.

Employing locals to grow food for the hungry on neglected land has an irresistible appeal, but it’s not clear yet whether Growing Power’s model can work elsewhere. “I know how to make money growing food,” Allen asserts. But he’s also got between 30 and 50 employees to pay, which makes those foundation grants — and a grant-writer — essential. Growing Power also relies on large numbers of volunteers. All of which perhaps explains why other urban farmers have not yet replicated Growing Power’s scale or its unique social achievements.

So no, Growing Power isn’t self-sufficient. But neither is industrial agriculture, which relies on price supports and government subsidies. Moreover, industrial farming incurs costs that are paid by society as a whole: the health costs of eating highly processed foods, for example, or water pollution. Nor can Growing Power be compared to other small farms, because it provides so many intangible social benefits to those it reaches. “It’s not operated as a farm,” said Ian Marvy, executive director of Brooklyn’s Added Value farm, which shares many of Growing Power’s core values but produces less food. “It has a social, ecological and economic bottom line.” That said, Marvy says that anyone can replicate Allen’s technical systems — the worm composting and aquaponics — for relatively little money.

Finished with his business in Merton, Allen sang out his truck window to his plastic-picking volunteers, “Don’t y’all work too hard now.” The future farmers laughed. Allen predicts that because of high unemployment and the recent food scares, 10 million people will plant gardens for the first time this year. But two million of them will eventually drop out, he said, when the potato bugs arrive or the rain doesn’t cooperate. Still, he was sanguine. “The experience will introduce those folks to what a tomato really tastes like, so next time they’ll buy one at their greenmarket. And when we talk about farm-worker rights, we’ll have more advocates for them.”

At a red light on Silver Spring Drive, Allen stopped and eyed the construction equipment beached in front of a dealership. “Look at that front-end loader,” he said admiringly. “That thing isn’t going to sell.” He shook his head and added: “Maybe we can work something out with them. We could make some nice compost with that.”

Elizabeth Royte is the author of “Bottlemania: Big Business, Local Springs, and the Battle over America’s Drinking Water.”

Copyright 2009 The New York Times Company

Elitist, arrogant, intolerant, self-absorbed.

Midliferider wrote:Wish I could wipe this shit off my shoes but it's everywhere I walk. Dang.

Pattio wrote:Never forget, as you enjoy the high road of tolerance, that it is those of us doing the hard work of intolerance who make it possible for you to shine.

xtian wrote:Sticking feathers up your butt does not make you a chicken

- DerGolgo

- Zaphod's Zeitgeist

- Location: Potato

What I find so darn fascinating about this whole GMO business is that even people like Norman Borlaug go on about how the whole world will starve without GMO crops...while, at the same time, GMO soybeans, for example, produce smaller yields per acre than the strains that farmers developed over generations of selective breeding.

Not only that, but genetic research has come to the stage where implanting one plant's genes into another is no longer really necessary. By identifying the desirable genes in one strain of a certain plant, traditional cross-breeding can be targeted to create the strain with the desired traits in a fraction of the time it used to take, but with much fewer risks than those associated with the genetic meddling (a commercially used strain of GMO potatoes was found to increase cancer rates in rats in Russia a while ago).

And how will the biotech revolution feed the world and make everyone happy when no one can afford to grow the stuff? Right now, farmers in India are going bankrupt over GMO crops. Wait a few years, and what do you want to bet that massive industrial agriculture will become the next big draw for the west to invest in in India and other places?

Right now, and for a number of years, the amount of food produced in the world, has been exceeding the amount needed to feed everyone. Distribution and money have been and are the reason there is still famine and undernourishment for many.

The problems that we actually have are the depletion of fish stocks in the oceans, destruction of arable land by erosion, pollution and soil exhaustion, agriculture subsidies in the west that prevent people in the developing world from feeding themselves and the big price tags that get slapped on food by the commodities markets.

And what do you want to bet that, eventually, they will go after people who grow their own food in their garden? Flick a GMO seed over the fence, get the lawyers in, make a bit of publicity and that little delight will go straight out of the window.

Right now, scientists are growing beef in petri dishes.

While that may not sound particularly appetizing, consider how much capacity for staple food production will be freed up when cows (and other tasty treats) are no longer fed with stuff grown instead of wheat, barley, potatoes, you name it.

Petri dish beef.

Once algae-biomass for fuel production becomes economically viable (it's getting closer everyday), no one will even consider the idea of wasting good, arable land to make fuel.

But while the last two are still in the future, there is a ton of things that can be done now to feed the world. Taking away farmer's independence (that worked well in Soviet Russia, didn't it...) isn't one of them. And multinationals shackling farmers to their products so they can divert a nice, big slice of agricultural subsidies into their own pockets isn't one of these things, either.

Monsanto and their ilk, the people who drive up prices on the commodities markets, the politicians that support them, they all should be in a Nuremberg style dock. Because taking away people's freedom to feed themselves is a massive crime against humanity, nothing else.

Not only that, but genetic research has come to the stage where implanting one plant's genes into another is no longer really necessary. By identifying the desirable genes in one strain of a certain plant, traditional cross-breeding can be targeted to create the strain with the desired traits in a fraction of the time it used to take, but with much fewer risks than those associated with the genetic meddling (a commercially used strain of GMO potatoes was found to increase cancer rates in rats in Russia a while ago).

And how will the biotech revolution feed the world and make everyone happy when no one can afford to grow the stuff? Right now, farmers in India are going bankrupt over GMO crops. Wait a few years, and what do you want to bet that massive industrial agriculture will become the next big draw for the west to invest in in India and other places?

Right now, and for a number of years, the amount of food produced in the world, has been exceeding the amount needed to feed everyone. Distribution and money have been and are the reason there is still famine and undernourishment for many.

The problems that we actually have are the depletion of fish stocks in the oceans, destruction of arable land by erosion, pollution and soil exhaustion, agriculture subsidies in the west that prevent people in the developing world from feeding themselves and the big price tags that get slapped on food by the commodities markets.

And what do you want to bet that, eventually, they will go after people who grow their own food in their garden? Flick a GMO seed over the fence, get the lawyers in, make a bit of publicity and that little delight will go straight out of the window.

Right now, scientists are growing beef in petri dishes.

While that may not sound particularly appetizing, consider how much capacity for staple food production will be freed up when cows (and other tasty treats) are no longer fed with stuff grown instead of wheat, barley, potatoes, you name it.

Petri dish beef.

Once algae-biomass for fuel production becomes economically viable (it's getting closer everyday), no one will even consider the idea of wasting good, arable land to make fuel.

But while the last two are still in the future, there is a ton of things that can be done now to feed the world. Taking away farmer's independence (that worked well in Soviet Russia, didn't it...) isn't one of them. And multinationals shackling farmers to their products so they can divert a nice, big slice of agricultural subsidies into their own pockets isn't one of these things, either.

Monsanto and their ilk, the people who drive up prices on the commodities markets, the politicians that support them, they all should be in a Nuremberg style dock. Because taking away people's freedom to feed themselves is a massive crime against humanity, nothing else.

If there were absolutely anything to be afraid of, don't you think I would have worn pants?

I said I have a big stick.

I said I have a big stick.

- Sisyphus

- Rigging the Ancient Mariner

- Location: The Muckworks

- Contact:

And ethanol sets up competition between food and powering vehicles.

I'm going on a guerrilla anit-marketing campaign, printing up stickers that I can surreptitously put on gas pumps while idly fueling my car/bike. They'll say, "Did you know ethanol blends are less efficient than regular unleaded?" And, "Ethanol comes from corn. Corn is an inefficient producer of ethanol." Or, "Growing corn repeatedly on the same land strips the soil of nutrients, necessitating the use of harmful fertilizers."

YOu know, stuff like that. I can print them up on my desk printer, no big deal at all.

I'm going on a guerrilla anit-marketing campaign, printing up stickers that I can surreptitously put on gas pumps while idly fueling my car/bike. They'll say, "Did you know ethanol blends are less efficient than regular unleaded?" And, "Ethanol comes from corn. Corn is an inefficient producer of ethanol." Or, "Growing corn repeatedly on the same land strips the soil of nutrients, necessitating the use of harmful fertilizers."

YOu know, stuff like that. I can print them up on my desk printer, no big deal at all.

Sent from my POS laptop plugged into the wall

-

motorpsycho67

- Double-dip Diogenes

- Location: City of Angels

- Sisyphus

- Rigging the Ancient Mariner

- Location: The Muckworks

- Contact:

It's already happening. Monsanto has successfully sued many small time farmers because their GM plants have shown up in neighboring fields. Said farmers refused to pay for these plants and then got hauled into court.DerGolgo wrote:And what do you want to bet that, eventually, they will go after people who grow their own food in their garden? Flick a GMO seed over the fence, get the lawyers in, make a bit of publicity and that little delight will go straight out of the window.

These plants are supposed to be "terminator" plants that can't reproduce, so the users have to repeatedly buy seed stock. Not so, says Mother Nature. They're cross-polinating on their own.

There's also a bill (don't remember the number) that will make it even harder for organic, small-time farmers and even people who grown their own food not for sale by regulating how the crops are to be grown within x feet of any livestock, something like 1 mile or somesuch bullshit, to minimize chances of contamination by E.Coli, allegedly. The bill is said to be heavily influenced by Cargill and Monsanto, ADM and so on.

Sent from my POS laptop plugged into the wall

-

motorpsycho67

- Double-dip Diogenes

- Location: City of Angels

Sisyphus wrote: I'm going on a guerrilla anit-marketing campaign, printing up stickers that I can surreptitously put on gas pumps while idly fueling my car/bike. They'll say, "Did you know ethanol blends are less efficient than regular unleaded?" And, "Ethanol comes from corn. Corn is an inefficient producer of ethanol." Or, "Growing corn repeatedly on the same land strips the soil of nutrients, necessitating the use of harmful fertilizers."

WANT!

'75 Honda CB400F

'82 Kawalski GPz750

etc.

'82 Kawalski GPz750

etc.

- Sisyphus

- Rigging the Ancient Mariner

- Location: The Muckworks

- Contact:

Avery Labels, the best tool for guerrilla marketing evar! Any size you want! Print at home!

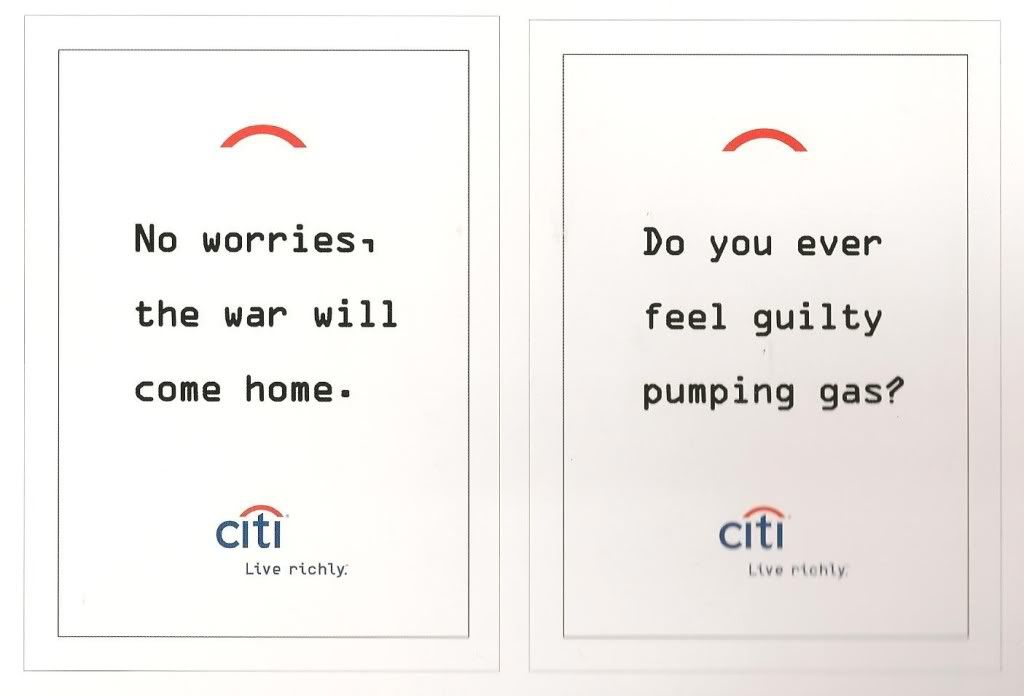

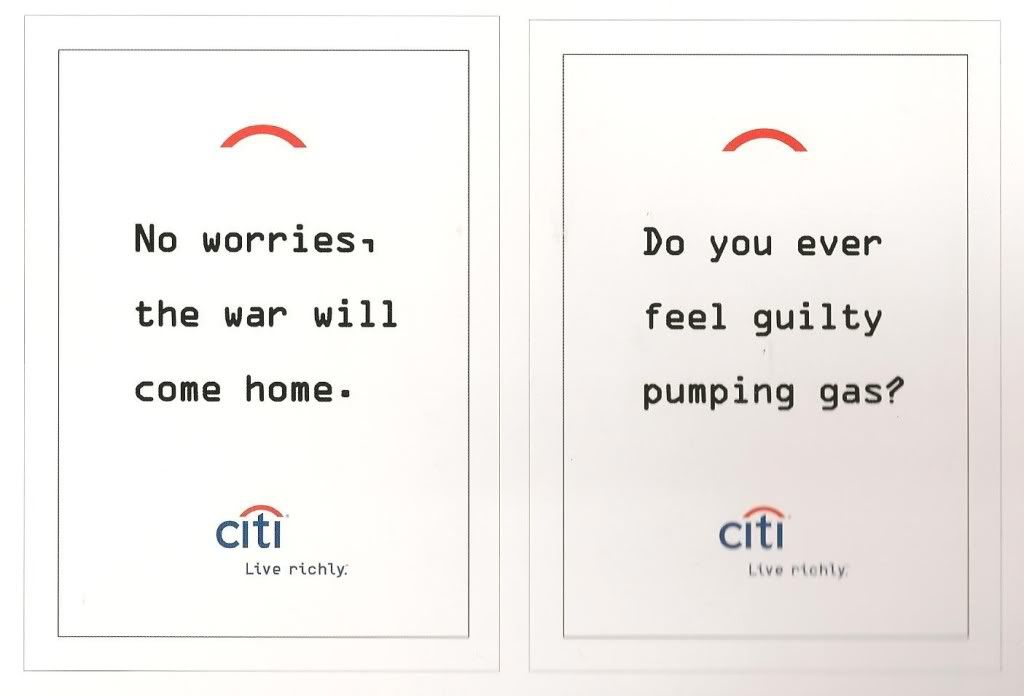

I got the idea from these:

Made by Copper Greene, they were dsigned to "catch viewers off guard, a parody of the widely recognizable Citibank campaign that promts cardholders to "live richly. It asks tougher questions and proposes bleaker answers than its less-political counterpart."

I got the idea from these:

Made by Copper Greene, they were dsigned to "catch viewers off guard, a parody of the widely recognizable Citibank campaign that promts cardholders to "live richly. It asks tougher questions and proposes bleaker answers than its less-political counterpart."

Sent from my POS laptop plugged into the wall

- Groove

- El Monstro De La Noche

- Location: Northern NY (The most North-ist part)

- guitargeek

- Master Metric Necromancer

- Location: East Goatfuck, Oklahoma

- Contact:

Elitist, arrogant, intolerant, self-absorbed.

Midliferider wrote:Wish I could wipe this shit off my shoes but it's everywhere I walk. Dang.

Pattio wrote:Never forget, as you enjoy the high road of tolerance, that it is those of us doing the hard work of intolerance who make it possible for you to shine.

xtian wrote:Sticking feathers up your butt does not make you a chicken